The Line Is Gone, but the Wait Remains

At the world’s oldest golf course, the Old Course in St. Andrews, Scotland, a new digital lottery replaces the legendary singles queue.

This is part I in a two-part series on how technology is reshaping the rules of access in golf.

St. Andrews is golf’s holy land.

Consider the Old Course at St. Andrews—the most famous, and the oldest, golf course in the world. Six hundred years ago, people gathered on this land, striking balls across the windblown dunes, shaping a game that would become what it is today.

For centuries, its fairways have been walked by kings and champions alike. King Edward VIII once fought its bunkers, Tiger Woods dominated it like no one before him, and Jack Nicklaus made his final exit at the Swilcan Bridge, the ancient stone footbridge connecting the first and eighteenth fairways. The Bridge is a monument to the game itself—a stage where champions pause, tip their cap, and let the golf world know: I was here. I made it.

A few hundred yards away, near the R&A headquarters—the governing body of golf outside the U.S. and Mexico—sits the 18th green, where Old Tom Morris, a man without whom the game would look very different today, rests eternally beneath the very turf where he revolutionized the sport.

The last part isn’t true: Old Tom Morris and his son, Young Tom Morris, are buried down the road at St. Andrews Cathedral. But here, you want to believe anything anyone tells you.

Unlike Old Tom and Young Tom, though, not all legends here are carved in stone. Some are whispered from golfer to golfer, passed down like scripture, growing more embellished with each retelling.

Among the whispered legends, none felt more enduring, or ridiculous, than the Old Course queue. To the uninitiated, it was just another absurdity of the game, one of those things golfers do that makes sense to no one but them. To those who did it, though, it was a rite of passage.

For three decades, wannabe golfers at the Old Course queued outside the Old Pavilion, near the first tee, in the dead of night, hoping to claim an unfilled slot. In 2016, a golfer visiting from Connecticut thought he had it figured out and set his alarm for 3:20 AM, convinced he’d be one of the first in line. When he arrived, there were 14 people ahead of him. Still, by morning, he’d secured a tee time, and by noon, he’d finished his round at Old Course.

“If you’re a golfer in St. Andrews with a day on your hands and don’t try to play the Old Course,” he wrote, “you should see a shrink.”

Some might argue that waking up in the middle of the night to stand in line is proof you already need one. But that’s golf—proof that irrationality isn’t just tolerated, it’s tradition.

Nostalgia only lasts as long as the people who can tolerate it.

In recent years, the queue had spiraled into an arms race of endurance—single golfers camping out for upwards of 12 hours, braving wind, rain, and exhaustion for a shot at playing golf’s most historic fairways. What was once a test of devotion had become a spectacle.

“The most we ever had queuing was over 80 people waiting outside,” said Gavin Fairweather, a longtime staff member at St. Andrews who works through the chaos of the singles daily draw. “We’d open up at 5:30 a.m., and it was madness—taking names, checking handicaps, and filling spots.

“People were bringing hammocks and pillows and duvets from hotels,” Fairweather added. “It wasn’t the image you wanted for the first tee at the Old Course.”

Last spring, St. Andrews Links Trust, which oversees the Old Course, replaced the queue with the singles daily draw, a “modern and equitable digital solution to its in-person singles queuing system,” the organization said in a statement.

No more huddled masses in the cold. No more strategic napping in the rain. No more bleary-eyed golfers watching the sun rise over the Swilcan Bridge, wondering if they were hallucinating.

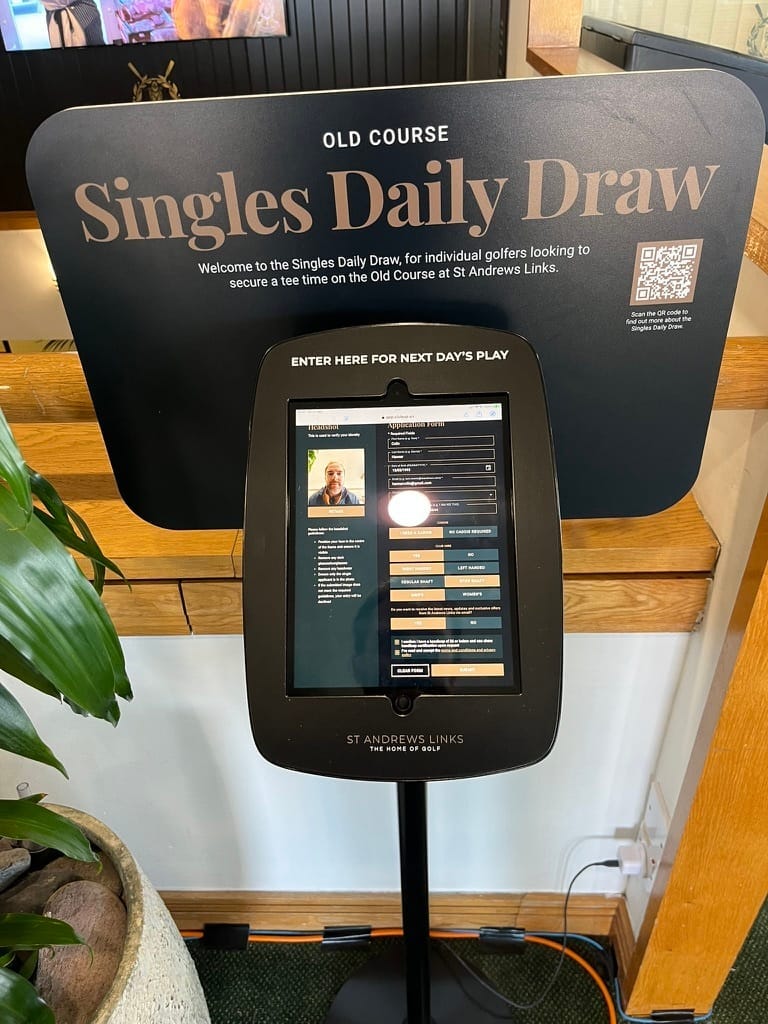

Single golfers—who had once relied on endurance—now had to physically enter the Old Pavilion or the St. Andrews Links Clubhouse between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. the day before they wanted to play and submit an electronic application from a tablet. At day’s end, a randomized draw determined which single golfers would fill open spots in the next day’s tee sheet.

Chance, not endurance, would now decide who got to play the Old Course.

Before this technological transition, I had imagined the ritual of securing a tee time at St. Andrews as textbook sanctimony: a test of devotion, a moment of blind faith.

Maybe a Scottish starter with a clipboard, a worn leather book filled with names, a knowing nod as he scribbled me into history. A whispered story from the golfer ahead of me, recounting the tales of his last time here, the best round he ever played, the friend who once got on as the very last name called. The reverence of watching the world wake up around you, the feeling that only exists when you’ve been awake long enough to see black fade to blue, when silence breaks into voices, when the dewed fairways catch their first morning footprints.

Instead, fresh off an hour-and-a-half rental car from Edinburgh, bleary-eyed from exhaustion and pure relief to have touched the pearly white gates of this version of heaven, I stood face-to-face with a greeter whose smile etched into wind-blown cheeks. Not unlike the starter I had dreamed.

“Hello! Welcome to St. Andrews,” he said.

“A single tee time for tomorrow?” I asked.

“Ah,” he said, unfolding his hands and gliding to his left to reveal—(!)—a metal stand holding an iPad. Like the kind you’d see at a doctor’s office. Or a bank kiosk. Or an airport lounge check-in. But now, inside the St. Andrews Links Clubhouse, just a few hundred steps from where guys with sticks whacked pebbles around the dunes half a millennium ago.

I tapped at the screen, entered my name, birthdate, phone number, and then, the final indignity—an awkward headshot, taken from below, forever looking down on my application to play the Old Course, as if I were peering over the edge of the green-side bunker on 12, staring down at what would soon be me, hacking my way out with abandon.

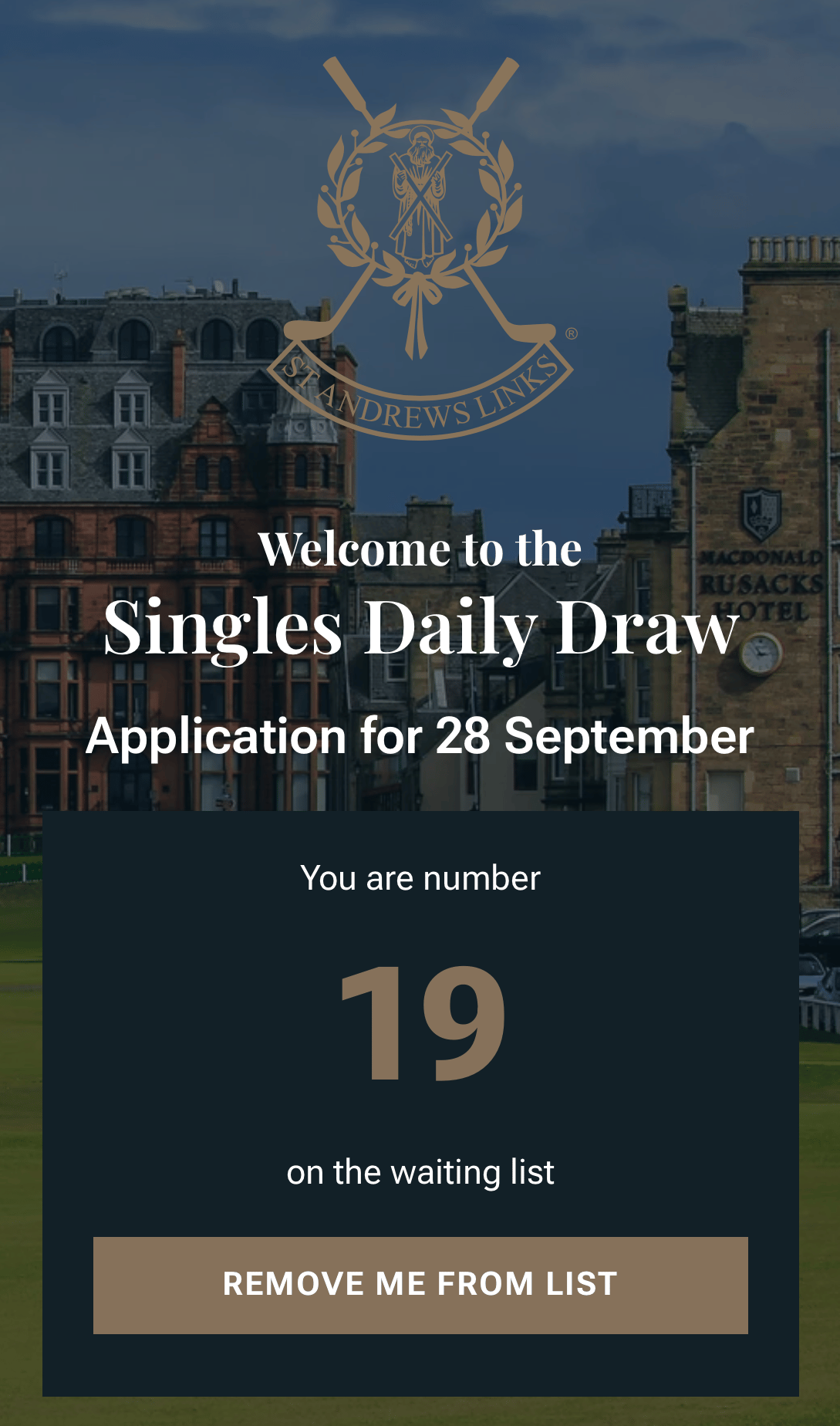

I hit “submit” on the screen, my fate at the hands of a randomized draw.

A few seconds later, my phone buzzed.

"Thank you for entering the Singles Daily Draw,” a text read. “We will advise you of the result after 5 p.m. via email and SMS, if provided."

And just like that—I was free? No standing in line? No huddling in the cold? No anxious countdown to a clipboard and a handshake? Golf makes you accustomed to the idea that to experience pleasure, you must first endure punishment. Or is that being raised Catholic? Unclear.

So, instead of waiting, Laura and I drove an hour to a bakery. I ate my breakfast slowly, drank my coffee without urgency, then we made the hour drive back to St. Andrews. By then, it still wasn’t 5 p.m.—the clocks are slower over here, it seems—so we checked into our hotel, wandered the town, stopped at a few shops. For a time, I stood near the 18th green, watching golfers finish their rounds, taking their own ceremonial walks across the Swilcan Bridge. Almost time, but not quite.

Later, sometime before 6, my phone buzzed—a text from an unknown number.

The moment of truth!

I opened it, scanning for the words “Congratulations.” Instead, consolations.

“You are number 27 on the waiting list.”

Defeated, but not ready to concede, I walked over to the Old Pavilion the next morning. I wasn’t going to play—not yet, anyway—but I still wanted to feel part of it. Some small, irrational part of me thought I might find a line of players wrapped around the building, golf bags standing next to them like a dog on a leash, waiting for their shot.

The Old Pavilion is a modest structure: a check-in counter, a café, a few high-top tables and barstools. Inside, it was buzzing golfers clustered around the front desk, flashing confirmation texts to staff members who nodded, typed, and occasionally called out names. Groups formed in real time, one from the States, another from Japan.

I ordered a coffee and took a seat. Maybe, just by being there, I’d get lucky. I watched, I waited, I checked my phone. I listened to golfers trade stories—where they’d played, where they hadn’t, who they’d been paired with.

At 7:15, the first person on the waiting list was called up to fill in for a person who hadn’t checked in for their tee time. I kid you not—people started clapping, congratulating the man as if he just had twins.

From there, the hour passed. Then another. Then another. Four hours in, I knew I should leave. The new system had given me the freedom to go on with my day, but I’d chosen to linger.

Eventually, I met Laura for breakfast, and we made a day out of a morning that hadn’t gone to plan—walking the seaside, letting the hours slip by.

But at 2:45 p.m., my phone buzzed. Whatever. Then it buzzed again. Hmm? I pulled it from my pocket: a call from a local number. I picked up.

“Hello, Colin?” a voice asked. “Calling from the Old Course. Are you available for a 3:20 tee off?” I can only assume my end of the line sounded like wind hitting the mic, because ten minutes later, I was on the first tee.

The starter warned us we probably wouldn’t finish with sunset was less than four hours away. Fine by me. Just let this dog off the leash and let him see how far he gets.

Laura walked with me as I played, and we were paired with a South African pilot living in Hong Kong who was here on a two-week golf trip and a husband-wife couple from the Upper West Side. We traded names, handicaps, and first-tee jitters, then settled into something looser, lighter. I played well on the front, had a triple bogey on the twelfth (that bunker…), and stopped counting anything but blessings after that.

The sky turned purple, then blue, then gone. We finished the last two holes in the dark, guided by the phone flashlights of the pilot’s friends, who had come out to walk the final holes with us.

It wasn’t perfect. It was better.

The wait used to happen outside. Now it plays out on a screen—a series of texts, emails, and calls—or, if you're stubborn, or chasing the nostalgia of a bygone era, over coffee in the same room where the notifications are being sent. What surprised me most was how little that seemed to matter. The stories, the hoping, the absurdity of it all—that all stayed.

We reach back for the good old days whenever the new ones feel uncertain. Today, more often than not, it’s technology that forces that reckoning—promising efficiency while quietly gutting the messiness, the meaning, the joy of not knowing. When that happens, it doesn’t just frustrate us. It’s a betrayal.

At St. Andrews, the Links Trust didn’t bulldoze tradition. They looked at what the singles queue had become: a test of endurance, yes, but also a health risk, a scheduling nightmare, and increasingly unfair to older or less able-bodied players.

“There are some people with a bit of a romantic notion about the singles queue, and they believe those who wanted it the most should be able to get out there,” David Connor, the St. Andrews Links Trust’s head of marketing and communications, told me. “But we don’t think playing the Old Course should be about survival of the fittest.”

So they kept the spirit and changed the system: You still have to be here, in town. You still enter in person. You still wait. “The banter is still there,” Gavin Fairweather, the Old Course starter, said. “It’s just moved from outside in the queue to inside the clubhouse.”

Elsewhere in golf, though, the charm has worn thin. Booking a tee time now means logging onto a course’s website at midnight, a month or two in advance, refreshing like mad, hoping to get in. But by the time the page loads, someone—or something—has already gotten there first. 🤖