For nearly three years, from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, Italian industrial designer and artist Luigi Serafini spent most of his time in his Rome apartment.

It was an “ascetic” life, Serafini told Bird in Flight in 2015, similar to that of a monk or a hermit. But born from the solitude was Codex Seraphinianus, an illustrated encyclopedia unlike anything that had been published before.

“The Codex was not a project in the conventional meaning of the word,” Serafini said. “To me, it was a necessity—I just had to do it. You may call it inspiration, but I would rather compare it to a state of trance. When you are in a trance, it doesn’t matter how much time you spend doing a job—you feel involved and can’t stop until you finish it.”

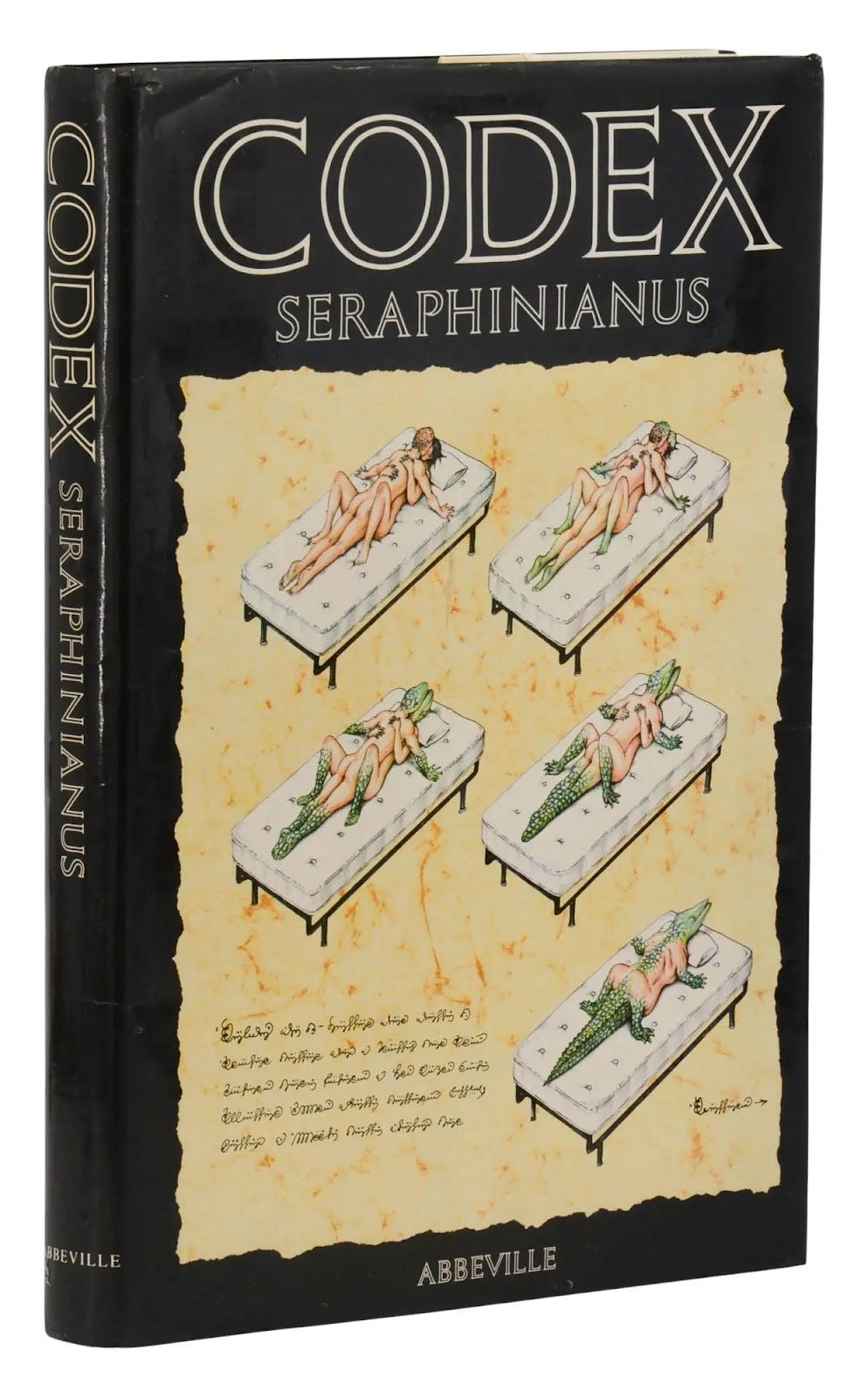

There are a lot of unconventional things about Codex Seraphinianus. It cannot be read, or rather, its words are an invented language, its alphabet is a bizarro style of calligraphy. Its images defy interpretation: On the cover of the first edition (above), what appears to be a man and a woman in a bound embrace morphs into a singular alligator.

For more than four decades, cryptographers and codebreakers have attempted to decipher Codex Seraphinianus to extract meaning from its nonsensical world.

Serafini, however, has always been clear: there is nothing hiding in plain sight.

“People wouldn’t believe my game—they needed a legend based on some kind of hidden meaning,” Serafini said. “A hidden meaning in itself was not enough—they needed a hidden meaning that could be deciphered. I don’t believe in such tricks.”

Though Codex Seraphinianus resists meaning, Serafini searched for it in his own life before going on this artistic journey. In the late 1970s, he traveled across the U.S.—a journey he’s compared to On the Road. And like Sal Paradise, Jack Kerouac’s protagonist, Serafini saw the world through a different lens. “I thought about things,” he said. “I made conclusions, told stories, and listened to the stories of others; I was changing myself and people around me.”

On this road trip, Serafini had a breakthrough, an epiphany, a far-out moment that brought about a feeling of himself in the world: “I felt I was a piece of information that existed in a certain network—a network created by the need for communication among over 70 million young people, a network that generated itself, because I was also one of those 70 million.”

Following the publication and success of Codex Seraphinianus—when the book was released in 1982, 5,000 copies were printed; in the secondary marketplace today, those first editions can be worth nearly $5,000—the concepts and the style of Serafini’s work can be seen in works spanning from books to films to video games. A Book from the Sky, for example, was published between 1987 and 1991 and is filled with language that resembles Chinese characters, but are in fact entirely meaningless. Director Guillermo del Toro’s sketchbook is filled with illustrations that could be mistaken for Codex Seraphinianus fanfic.

The surrealist logic—where meaning can exist and not exist at the same time—and the phantasmal scenes were something to be admired. For if a human could create something so deeply personal yet universally untranslatable, what does that say about us?

If a machine could do the same, what would that mean?

A few years ago, I thought of Codex Seraphinianus when experimenting with early versions of Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL-E—AI image generators that can produce intricate works with just a few carefully crafted prompts. It felt like the guardrails had come off of what a mildly tech-savvy person could create: the ability to conjure something from nothing, to make what had only ever existed in one’s imagination.

One of the early appeals—and one of its controversies—is the ability to generate artwork in the style of specific artists. You can Frida-fy an image, crank up the Van Gogh, or even put some Codex Seraphinianus on it. (The main image for this post is an AI-generated image of a person typing on a computer, looped over and over, “in the style of” Codex Seraphinianus.)

Serafi was not the first person to create an imaginary language, much less put it to page. Its Italian compatriot from centuries earlier, the Voynich manuscript, has perplexed cryptographers, historians, and scholars—including codebreakers from both World War I and II—for centuries. Is it a code or cipher? An encyclopedic index, or, like Codex Seraphinianus itself, an imaginary work of fiction?

Serafi was also not the first person to dabble in super-reality—or surrealism—a movement that supercharged reality with the unconscious mind.

Serafini, like any artist, was not the first to do many things. Instead, he was informed by works, the people, the places—everything—that came before him. He drew inspiration from illuminated manuscripts, surrealist traditions, scientific encyclopedias, and the nonsensical worlds of literary predecessors.

In this way, his process parallels AI—both reference the vast library of the world. But AI’s process of collecting differs fundamentally from human creativity.

We’re guided by learning, curiosity, daydreaming, experience, spontaneous observation. AI models generate based on probability—“creativity” is a series of weighted guesses based on prior input.

We invent because we feel something missing—an absence, a gap in understanding that must be filled. AI does not long for meaning; it does not create from uncertainty, only from probability.

We create from a lifetime of moments, failures, daydreams, and obsessions. AI creates from an enormous dataset, averaging the past into something plausible, but never personal.

Art isn’t just about borrowing references; it’s about bringing together concepts that might not naturally fit, forcing them into new and often uncomfortable juxtapositions, and in doing so, creating something singular. Codex does not neatly align with the traditions it draws from—it disrupts them, rearranges them, and reimagines them into something that could only come from Serafini’s mind.

AI-generated paintings may capture aesthetics, but they lack the depth of experience, a dilemma that’s playing out beyond visual art. The same is true in voice acting, where AI-generated performances mimic real actors but lack the spontaneity, emotional nuance, and lived experience that make a performance truly compelling. The result is something that sounds convincing on the surface but ultimately feels hollow.

Hank Azaria, the voice behind more than a dozen characters on The Simpsons, recently reflected on AI’s ability to replicate his work: “I imagine that soon enough, artificial intelligence will be able to recreate the sounds of the more than 100 voices I created for characters on ‘The Simpsons’ over almost four decades.”

Azaria argues that AI has the capability to mirror a “neck-up” version of humans, but that the “body and soul” will be harder to implement in these models. When, after being shown attempts of replicated voices, art, or books, we will start to see cracks in the presentation. “It adds up to a sense that what we’re watching isn’t real, and you don’t need to pay attention to it,” Azaria writes. “Believability is earned through craftsmanship[.]”

Even if we’re close to an era where we can document every part of ourselves and our experiences—and it often feels like we are, with stories capturing our highlights, trackers logging our movement, time capsules reminding us where we were one year ago—we still fail to capture the full spectrum of being human. The margins, the unconscious moments, still evade documentation.

And that, perhaps, is the real difference. “I, personally, am a riddle myself and any person is a riddle,” Serafini said, in response to why he made a whole book in a language no one can decipher, “and there is no absolute, undeniable meaning you can depend on when trying to solve those riddles.”

For all the ways it doesn’t appear of this world, Codex Seraphinianus may be the best representation of what it means to be human—not because it exists, but because of the road that led to it. 🤖